☜ Click for full post text.

This is one in a series of posts where the content is provided by a guest who has graciously answered five questions about their experience as a Tolkien fan.

To see the idea behind this project, or if you are interested in sharing your own, visit the project homepage. If you enjoy this series, please consider helping us fund the project using the support page.

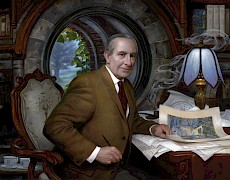

I want to thank Donato Giancola for allowing me to use his artwork for this project. Prints are available on his website!

Now, on to Catherine Madsen’s responses:

1. How were you introduced to Tolkien’s work?

I can’t improve on my mother’s account, though it’s a bit long:

“As for The Hobbit, I’ll have to take the credit or the blame for introducing you to that book. It happened like this. I was in a graduate library science seminar with my favorite L[ibrary]S[cience] professor one summer [probably 1961]. She divided the class up and gave us the task of coming up with a project that would enrich or strengthen our work and the profession. There was a children’s literature expert at Wayne [State] who was internationally known, named Dr. Eloise Ramsey. My partner and I decided we wanted to interview her and see what her recommendations were for the top, not to be missed, books for children. We would get her permission to duplicate the list and share it with the hundred or so school librarians in the seminar. There was only one problem. She had the reputation of being unpredictable, irascible and generally unapproachable. Certainly her image did not encourage queries. She had never read How to Dress for Success, but went around in cotton house dresses and socks. Our professor approved the project, saying that if we managed to get the interview it would indeed be a contribution.

“I was determined, after all I had another motivation, my darling daughter, for whom I wanted nothing but the best. My partner was game if I was. I made the phone call and very respectfully broached the project, stressing how helpful the bibliography would be. She made an appointment to see us and got so interested that she offered to give a presentation at the seminar, which was excellent and well received, and her top pick was The Hobbit.

“When it was sure we were going to Alaska I bought The Hobbit thinking that we would read it aloud evenings by the light of the Coleman lantern since it was also about a journey, but you wanted the familiar Wind in the Willows since you were dealing with the unfamiliar every day and I think you were right. Later when you were settled in you chose to read it and fell in love with it.

“p.s. The university hung on to Dr. Ramsey, socks and all, in the hope that when she died she would leave the library her fabulous children’s literature collection which she did.”

(Winifred Madsen, e‑mail correspondence 04 May 2012.)

My mother actually did read me the first several chapters during our first months in Alaska, making up tunes for the songs as she went along. By then I knew what a journey was, and pretty soon I devoured the rest of the book on my own and fell into a stupor of northernness from which I have never recovered. Inhaling The Lord of the Rings a year later only compounded it. This was in 1962⁄63, and I never met anyone else who had read the books (unless I told them to) until I went to college in 1969. There was one other family in Fairbanks that checked the books out of the library when I didn’t have them; I never knew who they were.

2. What is your favorite part of Tolkien’s work?

I can’t approach it that way; it’s like being asked to name your favorite piece of music. Reading The Hobbit and especially The Lord of the Rings, there in Alaska, changed me from an urban little girl all ready to be obsessed with boys and movie stars to an introspective kid with a religious sensibility and a feeling for trees and mountains. There’s a Yup’ik Eskimo expression I learned decades later, “When I first became aware”; it was like that, or like Wordsworth’s gaining a “sense of unknown modes of being.” The languages, the mighty landscapes, the sense of longing, the sense of loss — even the political tensions, like the bargaining over the Arkenstone or the strategic workings of Denethor’s mind — all of it added up to a world, a powerful source of strength and freshness and a moral demand. I felt trusted to have an intelligence and a soul.

3. What is your fondest experience of Tolkien’s work?

“Fondest” doesn’t quite compute, any more than “favorite.” Perhaps I need to go to the social level to answer that question. That would be my first meeting with the Tolkien Fellowship at Michigan State University. They had an annual Frodo and Bilbo’s Birthday celebration, which began with a walk in the campus woodlot while singing A Elbereth Gilthoniel to the English tune “Lovely Joan” (which Virginia Dabney, one of their founders, had swiped from Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on Greensleeves). I felt I had finally found my people. In the long run of course it was more complicated than that, but I’m glad I spent my college years with them and not with the druggies or the political radicals; in spite of the emotional upheavals and missteps common to young nerds, we had a kind of equilibrium, a sense of what mattered. That remains, whenever I’m in contact with one of those people — a profound core of shared experience and mutual understanding.

4. Has the way you approach Tolkien’s work changed over time?

Certainly — there’s a great difference between an eleven-year-old swept away by the beauty of language and imaginary landscapes and an adult with critical faculties and a wider experience of literature. But Tolkien holds up to adult sensibilities better than I feared he might, and perhaps (for a certain kind of kid) even helps to develop adult sensibilities. By the time I was fourteen I had tracked down “The Monsters and the Critics” and “On Fairy-Stories,” and being primed by the imaginary scholarship of the appendices I was excited to encounter real scholarship for the first time. When I was in my twenties Tolkien’s letters appeared, and I was moved to see the sophistication and humanity of his political thinking and the range of his interests. It’s been a pleasure (and a relief) to see Tolkien criticism become more and more substantive.

Perhaps the thing that most strikes me now is the sense of Tolkien’s voice as a father’s voice — not just the silly authorial asides in The Hobbit or the weaving-in of themes and characters and phrases and in-jokes from The Hobbit into The Lord of the Rings, but the way the story grows from a homelike amusement to something big and dangerous, so that by the time you’ve finished you’ve had a full course in responsibility and moral gravity and intercultural tensions and making decisions without enough information and living with the consequences, and humility and wonder and hope and brokenness and heartbrokenness and bereavement. He’s a father who wants you to grow up. That doesn’t mean the story is only for children; it means there are discoveries to make in it even as an adult.

5. Would you ever recommend Tolkien’s work? Why/Why not?

Always.

There will always be people who won’t like it — who are too guarded, for one reason or another, to sense its complexity and power — but it’s now clear that there are people all over the world who are moved and somehow guided by it, and I wouldn’t want anyone to miss the chance of reading it in case it might take them in that way.

You can read more from Catherine Madsen on her blog!